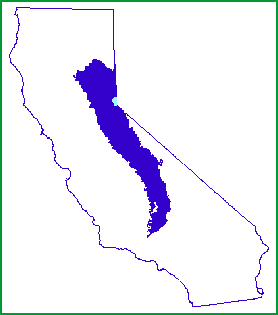

The Sierra Nevada mountains form an unbroken 400-mile-long wall running north to south in eastern California, between the Central Valley to the west and the Basin and Range physiographic province (including the Mojave Desert) to the east.

The Sierra Nevada mountains form an unbroken 400-mile-long wall running north to south in eastern California, between the Central Valley to the west and the Basin and Range physiographic province (including the Mojave Desert) to the east.If you were to approach the Sierra from their western foothills they appear tame, rising gradually over many miles of wooded and well-watered terrain. But if you approach from the east--as I did--be prepared for a shock...the mountains rise abruptly from the valley floor, ascending quickly to heights unattained anywhere else in the contiguous United States. Here on the eastern side, the tameness of the western slope is totally absent. The Sierra Nevada mean business.

I first met the Sierras up close at the town of Lone Pine (N36.604 W118.062). Just west of here Mount Whitney rises 2 miles above the valley floor. At 14,505ft (4,421m) in elevation, this is the highest peak in the Lower 48. Interestingly, it is just 76 miles from Badwater Basin (see my previous post), the lowest point in North America.

N36.57959 W118.29250

For the next 185 miles I will be following US Highway 395, running parallel to the eastern slope of the mountains. Along the way there are several signs indicating the passes which lead over to the western side of the Sierras. But all of these are still closed for the winter. The mountains are impenetrable for nearly 200 miles.

The map tells me that I am in the Owens River Valley. Odd, but as I write this post several weeks after being there, I do not once recall seeing the Owens River. Maybe this is because I was driving in the dark evening hours, or... perhaps I arrived a century too late?

The map tells me that I am in the Owens River Valley. Odd, but as I write this post several weeks after being there, I do not once recall seeing the Owens River. Maybe this is because I was driving in the dark evening hours, or... perhaps I arrived a century too late?The Owens River's natural terminus is Owens Lake, a few miles south of Lone Pine. In existence since the Ice Age, for millenia it was a haven for migratory birds. In historical times it was 10 miles wide, 15 miles long, 30 feet deep. A steamship crossed it. I have to use the past tense, though, because Owens Lake is no more: since 1924 it has been reduced to a dry salt flat which creates noxious alkali dust storms.

The agent of its demise was an aqueduct, completed in 1913, which diverted the Owens River's flow to the city of Los Angeles 250 miles away. The diversion of the river and the disappearance of Owens Lake remain highly controversial, at the heart of the California Water Wars and the subject of a book (which I am currently reading), Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner.

Further north, not far from the town of Mammoth Lakes is Lake Crowley, a resevoir built in 1941 by the City of Los Angeles. It is named for Father John J. Crowley, a Catholic priest who devoted himself to improving the lives of the residents of the Owens Valley after the diversion of the river drained life from the valley. I will have more to say on this topic in an upcoming post about Mono Lake. So, moving on for now...

Before leaving Oakland, Susan lent me a book describing the many rustic hot springs (露天風呂 "rotenburo" in Japanese) in the eastern Sierras. I decide to visit one called Hilltop Hot Spring, just five miles from Lake Crowley, at about 6AM. It was a little hard to find, but well worth it. The warm water was very soothing and the mountain views were great. Highly recommended!

N37.662 W118.781

Next: Mono Lake

No comments:

Post a Comment